Introducing ‘Pataphysics: the science of imaginary solutions

About mocking observable and measurable ways of knowing

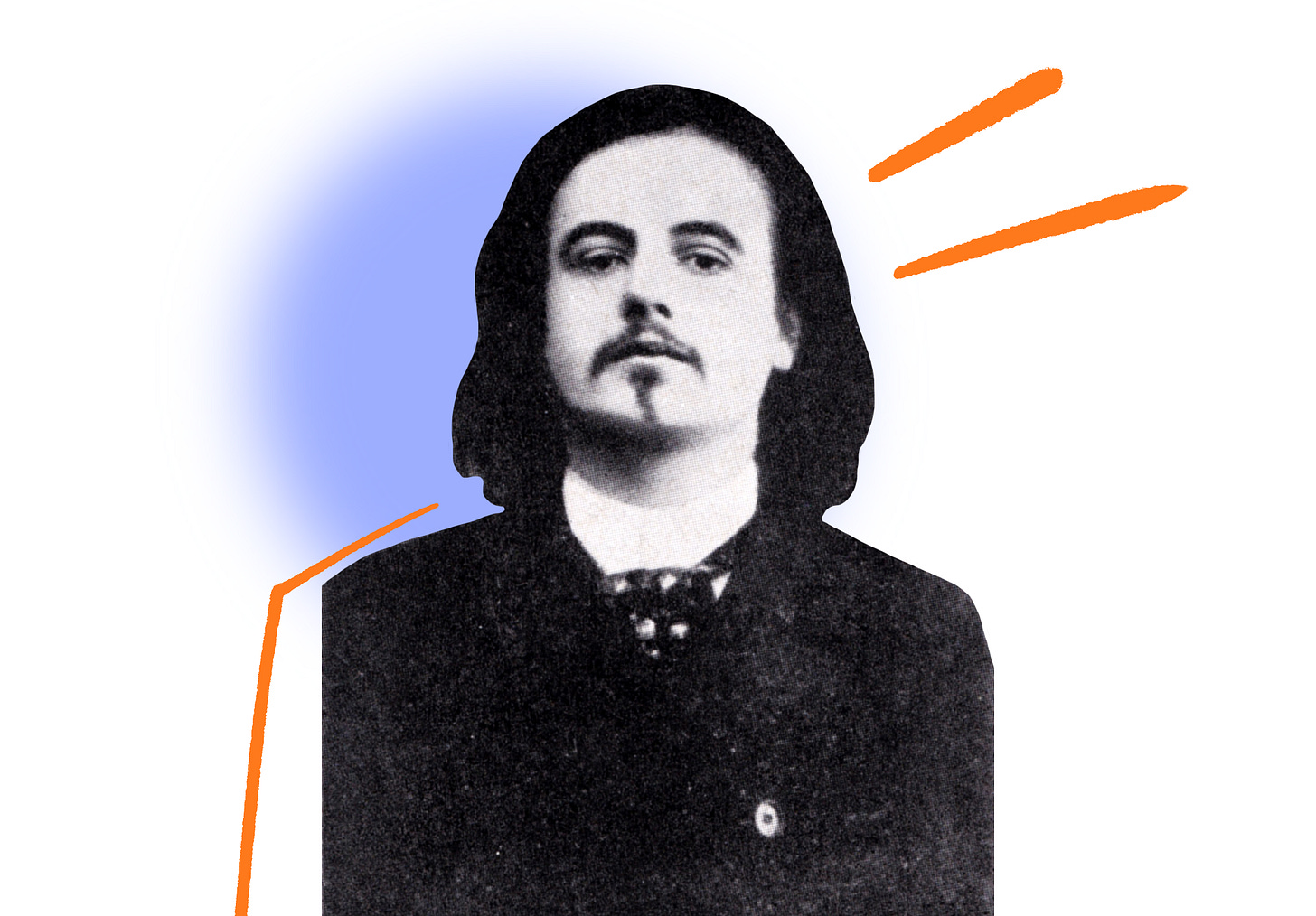

Pataphysics is a late 19th-century movement founded by the French novelist and writer Alfred Jarry (1873-1907). He characterized pataphysics as “the science of imaginary solutions”, intended as a parody of science1. The movement aimed to challenge conventional interpretations of reality, carried out through humor, often in the form of absurdism.

Pataphysics emerged as a critical response to positivism, the dominant philosophy of science at that time. Positivism developed through several stages known by various names, such as logical positivism and logical empiricism2. In its essence, positivism advocates that reality is measurable and encompasses only what one can directly observe3. It believes that knowledge is rooted in sensory experience and scientific methods and should focus on observable and measurable phenomena, rejecting other ways of knowing such as intuition or speculation.

Pataphysics, on the other hand, critiques this rigid framework by embracing other ways of knowing. It posits that reality is not limited to what can be empirically observed and measured. Instead, pataphysics views reality as a human construct, without a singular truth that is directly observable. It celebrates the exceptions and the imaginative possibilities that positivism tends to dismiss. By doing so, pataphysics challenges the notion that positivism is the only valid path to understanding the world.

“Pataphysics will be, above all, the science of the particular, despite the common opinion that the only science is that of the general. ‘Pataphysics will examine the laws governing exceptions, and will explain the universe supplementary to this one; or, less ambitiously, will describe a universe which can be - and perhaps should be - envisaged in the place of the traditional one.”

Alfred Jarry

In the mid-20th century, the Collège de ‘Pataphysique in Paris became a hub for artists and intellectuals who identified themselves as Pataphysicians. As a society committed to “learned and useless research”, they were dedicated to exploring and applying the pataphysical philosophy through a variety of practices, such as literature, fine arts, theater, and pseudoscience.

The term pataphysics first appeared in Jarry’s play Ubu Roi. This bizarre and comic play about the grotesque and tyrannical character Père Ubu left its audience shocked. Ubu Roi was a satirical critique of the French bourgeoisie and significant for the way it mocked cultural rules, norms and conventions. It opened up the door for modernism in the 20th century and is seen as a precursor to movements like Dadaism, Surrealism, and the Theatre of the Absurd, pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable in art and performance4.

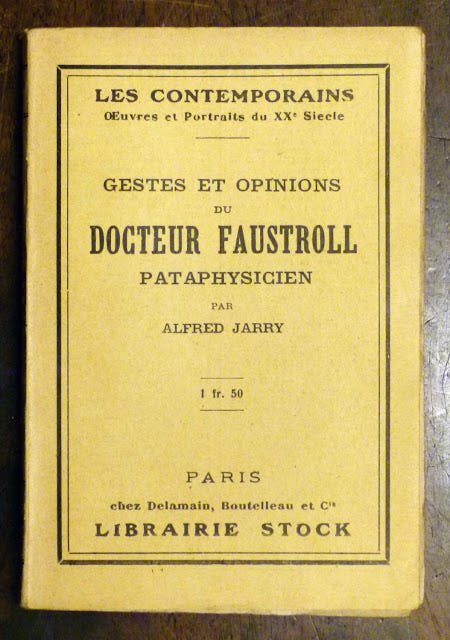

Another notable example of pataphysical work is Jarry’s novel Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician. Published posthumously in 1911, this novel features Doctor Faustroll, who embarks on a voyage “from Paris to Paris by sea.” Despite dying during his adventures, Faustroll undertakes the ultimate pataphysical experiment: determining the surface and nature of God, which he concludes to be “the shortest distance between zero and infinity.” This novel exemplifies the pataphysical approach of combining scientific rigor with absurdity to critique conventional scientific paradigms. By attempting to quantify something inherently unquantifiable, Jarry highlighted the limitations and absurdities of empirical approaches to understanding reality.

🌀 Next time I will write about pataphysics in design. That promises to be fun!

Hugill, A. (2012). ’Pataphysics: A Useless Guide. MIT Press.

Blumberg, A. E., & Feigl, H. (1931). Logical Positivism. The Journal of Philosophy, 28(11), 281. https://doi.org/10.2307/2015437

Shannon-Baker, P. (2023). Philosophical underpinnings of mixed methods research in education. In International Encyclopedia of Education (Fourth Edition) (pp. 380–389). Elsevier. https://doi org/10.1016/b978-0-12-818630-5.11037-1

Berghaus, G. (2000). Futurism, Dada, and surrealism: Some cross-fertilisations among the historical Avant-gardes. In International Futurism in Arts and Literature (pp. 271–304). De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110804225.271